“Knights of the KKK,” a Klu Klux Klan baseball team. 1957.

I am deep in the throes of a late-onset obsession with Major League Baseball. The combined factors of living a pleasant, partially above-ground subway ride away from the stadium where my favorite team plays, their having had an improbably good season in 2015, and finding myself in dire need of an outlet for naturally anxious emotional tendencies besides the very fate of our nation… have ignited in me a deep and (often) deeply satisfying fandom—propelled by the zeal of the lately converted. If I’ve already bored you with this stuff in person, I’m sorry, and know that I will eventually be talking about politics.

There is a lot to love about baseball—the oblique communications between pitchers and catchers; the Homeric feats of batting and symbiotic dance of defensive play; the satisfying empiricism of advanced metrics set against the ever more distant horizon of “that which can’t be quantified;” the real-time descriptive poetry of a good radio broadcast; the comfort and reliability of a long, steady season; the feeling of mild vertigo when, upon emerging from the beer and hotdog musk of a stadium’s cement peripheries, you first glimpse the improbable expanse of green at its center; the gulp of fresh air at that moment; the aesthetic disorientation of enjoying a slow pastoral game in a hurried urban setting, etc. etc.—but as I’ve come to accept and embrace my new mania, I’ve also had to face the uncomfortable fact that baseball is, in obvious and less obvious ways, America’s most conservative sport.

There’s a very literal sense in which this is true. Baseball team owners are almost exclusively white men with money, much of it ill gotten (at least by my standards)—in real estate, investment banking, oil and gas. (Baltimore Orioles owner Peter Angelos, who made his first million suing asbestos manufacturers, is a notable exception.) And they tend to tailor their politics accordingly. During the 2012 election cycle, MLB club employees, members, and ownership groups gave $24 million to politicians, PACs, and independent expenditures. Seventy-five percent of those donations went to conservative causes.

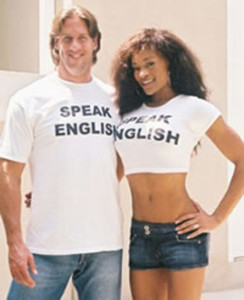

And while rich white guys also own most NBA (98%) and NFL (97%) teams, the dominant politics of the players in baseball are conservative too. Former Yankee greats Paul O’Neill and Johnny Damon both recently endorsed Donald Trump for president. Ditto Pete Rose and former Atlanta Braves hurler John Rocker, known during his era for an extraordinarily racist and homophobic screed against New York in Sports Illustrated, and more recently for wearing and selling “Speak English” t-shirts and pointing to his non-white girlfriends as evidence that he’s “not a Republican in everything.” (I’m not going to unpack that for you. I’m sure you’ll do just fine.)

It’s not that every player in baseball shares the politics of Rocker, O’Neill, Damon, or “second baseman” (his words, not mine) Daniel Murphy, who told reporters he “disagrees” with the homosexual “lifestyle” after gay ex-player Billy Bean visited Met’s spring training camp in 2015. Conservative politics are dominant in the hegemonic, if not in the statistical sense. Mets broadcaster Ron Darling, one of MLB’s rare out-and-out liberals, says he “always felt tons of pressure not to express [his] liberal views, and/or opinions” as a player in the 80s. “Clubhouses, at least in my experience, tend to be right of right,” says Darling. Fernando Perez, a former Tampa Bay Rays outfielder and another liberal (also possibly MLB’s only avowed fan of Robert Creeley), says that for every Rocker or Damon, there are a handful of players in the club who share their politics but don’t say so to the media. “Murphy probably got so much love at second base last year from guys who commended him for his courage to stand up to gays, while patting him on the ass,” Perez told the Daily News.

But there is a more insidious and, in my judgment, destructive way in which Major League Baseball expresses and enforcing its conservatism: through what are called its “unwritten rules.” These tacit norms constrain how players are permitted to act on field, with an emphasis on stoicism, emotional restraint, and humility. Violate these rules—ostentatiously celebrate an out, flip your bat after a big hit, or stand and watch a homer fly instead of diligently rounding the bases (termed, in the blue parlance of an all-male workplace, “pimping”)—and an opposing pitcher just might sock you with a 90 mile-an-hour fastball the next time you’re up. The unwritten rules are affective demands, concerned with how players should and should not move their bodies, and they’re enforced by the threat of pain.

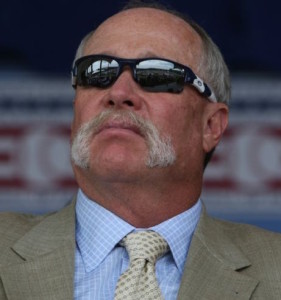

Recently, a reporter made the mistake of asking Hall of Fame reliever Goose Gossage a question. Gossage, no stranger to giving clouds a piece of his mind, but also a widely respected baseball veteran, took the opportunity to call Toronto Blue Jays superstar Jose Bautista, a “fucking disgrace to the game” for violating baseball’s norms of propriety. Goose said Bautista’s infamous bat flip during Game 5 of the ALDS was “embarrassing to all the Latin players who ever played before him.” He also name-checked Mets’ outfielder Yoenis Cespedes, presumably for doing this:

It’s not a coincidence that Cespedes is Cuban and Bautista Dominican. These flare ups of concern about the erosion of baseball values—translation: that baseball players occasionally act like they’re having fun—almost always center on non-white players’ perceived violations of baseball etiquette. Gossage’s comments are plainly racist. But the fact that this handlebar mustachioed white man is prone to racial prejudice is less troubling than the fact that his comments do not (at all) contradict the presiding ideology in baseball. They reflect it.

Put simply, baseball’s unwritten rules—like many other American norms—are selectively enforced. The longer you’ve been in the game and the whiter your skin, the easier it is to get away with peacocking without taking a ball to the ear. Whereas, if you’re black or brown, the smallest gestures of triumph can be construed as provocations—by opposing players, managers, and fans alike.

During the NFL playoffs, when white America was feeling scandalized by Cam Newton’s unapologetic blackness, I was reminded (yet again) how indispensable a lens is sports for understanding race and racism in America. Nowhere in American culture is the white demand for black propriety and deference more clearly articulated than in sports. The negative reaction of white fans and writers to Cam Newton’s dancing, his fashion, his arrogance, and his talent is difficult to interpret as anything other than a basic hostility toward black joy and exuberance.

In baseball, the dynamics are the same, only worse. In the MLB—where 61 percent of players, 87 percent of managers, and 83 percent of the fans are white—the cultural authority of the Old Guard is much less thoroughly eroded than it is in the NFL or NBA. Cam Newton was scolded for elaborate dances and dabbing in the end zone. Meanwhile, Bautista, Cespedes, and others are criticized for bat flips—for doing literally the best thing you can do in baseball, and then tossing the implement with which they did the best thing with too much oomph.

Meanwhile, Manny Machado, a 23-yr-old Dominican player, took a fastball to the shoulder (it was headed for his head) for doing this:

You didn’t miss anything. That was it. Jonathan Papelbon, a 35-yr-old white pitcher, himself not exactly a paragon of decorum, decided Machado had expressed too much elation after hitting this go-ahead homer, his thirtieth of the season. So, two innings later, he plunked him.

Explaining why black athletes and fans have abandoned baseball (and they have), comedian Chris Rock said that anti-celebration codes make baseball “like a visit to the queen—if you don’t bow correctly it could be an international incident.” The authoritarian tones of the analogy are apt. Enforcing traditional codes of conduct is the primary way that whiteness continues to exert its authority over the game. When baseball old-timers talk about the “right way” to play the game, they mean the “white way.” And in this, I see less a genuine loyalty to the game’s existing norms, than an attachment to the privilege of defining what those norms are.

No other baseball league functions this way. As the New York Times reported—with pearls firmly clutched—during the World Baseball Classic in 2013:

“The Dominican Republic has celebrated every hit as if it were its last, every putout as if it had decided the game. Its players have clenched their fists, pounded their chests and screamed — sometimes in the fourth inning. And if the Dominicans took a late lead, the whole dugout would explode, players bursting onto the field, like confetti out of a party popper.”

This is closer to how baseball is treated in Japan, Venezuela, Puerto Rico and other parts of Latin America. It’s not the staid, genteel affair it is (or is supposed to be) here. South Korean players have elevated the bat flip into an art form.

In the baseball mainstream, these discrepancies are often explained as “cultural differences,” usually with a scarcely concealed nod to stereotypes about naturally “hot” Latin temperaments. The growing number of players from Latin America simply have to be taught the American way, they say.

But the oppressive nature of American baseball is not about preserving something essential about American culture. It’s about control. Or perhaps more accurately, the core value being preserved—cloaked in a demand for gentility—is control itself. Put simply, baseball’s unwritten rules are about disciplining unruly non-white bodies.

This subtext was made text by white San Diego Padres pitcher Bud Norris in an interview with USA Today in October 2015. After complaining about Astros outfielder Carlos Gomez, a Dominican player known for inspiring the ire of opponents with home run celebrations and the occasional taunt, Norris said this:

“This is America’s game. This is America’s pastime… We’re opening this game to everyone that can play. However, if you’re going to come into our country and make our American dollars, you need to respect a game that has been here for over a hundred years… I understand you want to say it’s a cultural thing or an upbringing thing. But by the time you get to the big leagues, you better have a pretty good understanding of what this league is and how long it’s been around.’’

Norris’s message to his foreign-born colleagues is plain: your safety and security here is contingent. You owe us your deference, your compliance. This is our game; you’re only playing it.

On the bright side, the fact that the Goose Gossages of baseball are honking (and have been for years) is evidence enough that their dominance is slipping. More and more players and fans are sick of the unwritten rules, which hamper the excitement of a game already considered “too boring” for the 21st century. Bryce Harper, one of the two best players in baseball and a nationally known baseball prodigy from the age of 12, recently told ESPN The Magazine, “Baseball is tired. It’s a tired sport, because you can’t express yourself. You can’t do what people in other sports do.”

What are kids playing these days? Football, basketball. Look at those players — Steph Curry, LeBron James. It’s exciting to see those players in those sports. Cam Newton — I love the way Cam goes about it. He smiles, he laughs. It’s that flair. The dramatic.”

Harper, who is white and 23, praised players like Andrew McCutcheon, Jose Fernandez, Yasiel Puig, and Manny Machado for making the game exciting with their willingness to emote on the field. Harper has had his own disciplinary run-ins with the baseball Old Guard. Last season, Jonathan Papelbon choked (yes, choked) Harper, his teammate, in their dugout for…well, either for not running out a pop-fly or for being really good and young and arrogant or for criticizing Pap over beaning Machado. Unclear. Probably all of those things. (Not insignificantly, at least one reporter found a quorum of “current and former” players who backed Pap in the dispute. They wouldn’t go on record.)

Charles Krauthammer, rightwing pundit and crap human, explained why so many conservative thinkers enjoy baseball thusly:

“Bill Buckley once said his mission in life was to stop the world. Well, modern conservatives don’t want to stop it, they just want to slow it down and the perfect model is baseball.”

There’s something to this. Baseball acquired its status as America’s pastime in the 20th century because it embodied a national nostalgia for quaint pastoralism in a rapidly industrializing world. In this formulation, baseball—like conservatism—looks back. It yearns for a return to a lost time of simplicity and plenitude. (Of purity.)

But as intellectual historian Corey Robin has convincingly argued, conservatism’s nostalgic symbolic politics are always subservient to its more fundamental end: defending established hierarchies against dissent. What looks like an investment in preserving traditions, is really an investment in preserving traditional authority.

I don’t think baseball is an essentially conservative sport. But I do think it is an institution rife with hierarchies, resistant to change. Jose Bautista’s bat flip, Manny Machado’s swagger, Andrew McCutcheon doing the worm at first base—these moments aren’t just entertaining. They’re acts of defiance against the existing power structure in baseball—fugitive moments of joy, stolen from a hegemonic order of players, ex-players, managers, and fans who would sooner see baseball’s relevance wane than surrender authority over its meaning. In their fear of relinquishing control to a younger, less-white generation, baseball’s conservative hegemony imposes sterility and punishes joy, feeling, and sincerity. It’s tired. Very tired.

The truth is that baseball’s future—like America’s—belongs to and depends on young people of color. Most reasonable people in baseball know this, whether or not they welcome the fact. May the old order tremble at the sounding of their bat flips.