For the last few months, Langston Hughes’s depression-era poem “Let America Be America Again” has been playing in my head.

The poem has something of a promiscuous political history. John Kerry used the its title as a campaign slogan in 2004; Scott Brown, in a 2012 campaign ad. In 2011, it appeared on Rick Santorum’s website, before the anti-gay Santorum learned more about Langston Hughes and scrapped it. Now, of course, you hear its echoes in Trump’s ubiquitous refrain. Both evoke an America that was, that can be again. It begins:

Let America be America again

Let it be the dream it used to be.

Let it be the pioneer on the plain

Seeking a home where he himself is free.

This first voice is nostalgic and patriotic. Trumpian. But interrupting it is another voice, sullen and blunt:

(America never was America to me.)

Two more stanzas follow this pattern. The first voice sings the praises of “that great strong land of love” where “opportunity is real, and life is free, where “equality is in the air we breathe.” And again the other voice interrupts: “(It was never America to me)”; “(There’s never been equality for me, nor freedom in this ‘homeland of the free.’)”

Finally, the first voice addresses the second, venomously:

Say, who are you that mumbles in the dark?

And who are you that draws your veil across the stars?”

Here the second voice escapes its parentheses and carries the remainder. “I am the poor white, fooled and pushed apart,” it says, “the Negro bearing slavery’s scars… the red man driven from the land.” The second voice tells another American story, one that contradicts the pastoral hopefulness of the first, a story in which exploitation and subjugation have been the norm, where the rich “live like leeches on the people’s lives.” There is no America to redeem because America never was.

Not incidentally, the politicians who’ve channeled Hughes’s poem have dwelled on the first rather than the second voice. When John Kerry quoted several lines from “Let America be America Again” at the 50th anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education in Topeka, Kansas in May 2004, he skipped over the second voice altogether.

We know why. The second voice unsettles; speaks out of turn. Drawing her veil across the stars, she casts an unflattering shadow on America’s self-image. The second voice refuses to succumb, even briefly, to the seductive comforts of an illusion. It’s a lovely story, she says, but it isn’t true. American was never America to me.

This, it should be said, is a courageous act. It’s dangerous to contradict the myths of the comfortable—especially when they’re singing.

* * *

On August 27, at a preseason football game in Santa Clara, California, San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick remained seated during the national anthem. He told the media afterward, “I am not going to stand up to show pride in a flag for a country that oppresses Black people and people of color.”

“There are bodies in the street,” Kaepernick added, “and people [are] getting paid leave and getting away with murder.”

A few hours later, a 49ers fan filmed himself burning Kaepernick’s jersey in effigy. Other fans soon followed suit. In one video, Kaepernick’s #7 jersey hangs from a tree, engulfed in flame, as an orchestral recording of the anthem plays in the background. The fan holds his hand over his heart as the jersey turns from red to coal-black and falls to the ground, as if on cue, when the horns sing “home of the brave.”

Over the past two months, Kaepernick’s anthem protest has spread to dozens of other NFL players, and to college, high school, and youth athletes. Meanwhile, the vitriol against Kaepernick has reached a fever pitch. At a 49-ers game in Buffalo a few weeks ago, Bills fans sold t-shirts in the parking lot imprinted with an image Kaepernick’s face framed by crosshairs and the words “Wanted: Notorious Disgrace to America.” He has begun receiving death threats.

Where Kaepernick’s critics see an insult to the nation’s symbols, his supporters see the highest expression of patriotism. For them, holding the nation accountable to its purported values is what patriotism consists of. As MTV’s Jamil Smith wrote, channeling Baldwin, Kaepernick’s actions demonstrate how “the greatest love for our nation is shown by those who seek to improve it.” “I’m not anti-American,” Kaepernick has said, “I love America. I love people. That’s why I’m doing this. I want to help make America better.” After the first wave of reaction, Kaepernick and his allies opted to kneel instead of sit during the anthem—a gesture, in its execution, not unlike supplication.

But none of this matters to Kaepernick’s frothiest white critics. Anti-racism doesn’t figure in their definition of patriotism. Quite the opposite. For them, the image of a Black man refusing to submit, refusing to show sufficient passivity, gratitude, deference, is intolerable. It’s not only unpatriotic; it’s un-American.

I’ve wondered lately—and especially since America elected an unrepentant white nationalist as president—whether there isn’t some perverse wisdom in this view. The question of whether it’s possible to criticize American racism without implicating something deeper, something at the root of American identity and history remains unsettled. As Wesley Morris observed recently, “Whiteness and America have always been kept synonymous, conjoined, fiercely paired.” Can we indict the former without incriminating the latter?

Colin Kaepernick’s critics seem to believe that to protest racism—no matter how cautiously—is to protest America. Perhaps they’re right.

* * *

On March 21, 2008, Bill Clinton was speaking at campaign stop for Hillary Clinton in Charlotte, North Carolina. Envisioning a general election between his wife and John McCain, Bill said, “I think it would be a great thing if we had an election year where you had two people who loved this country and were devoted to the interest of this country, and people could actually ask themselves who is right on these issues, instead of all this other stuff that always seems to intrude itself on our politics.”

His meaning was clear enough. Obama’s patriotism—his Americanness—had long been the subject of suspicion. Right-wing radio hosts emphasized his Arabic middle name and speculated he had taken his oath of office on a copy of the Quran. A photo circulated on right-wing listservs of Obama with his hands clasped below his navel, instead of over his heart, during the national anthem. Debate moderators grilled him about American flag lapel pins. And always, the question of his relative patriotism was linked to that of his blackness.

With one sentence, Bill had fueled the popular perception that Obama wasn’t quite America-loving in his worldview, while simultaneously lamenting that controversies about his race and origins were distracting from the real issues of the campaign. It was a common maneuver among Obama’s tactful detractors in the waning days of the 2008 primary: not that Obama’s blackness was disqualifying of course, but that it was too controversial, maybe even dangerous. (A few weeks later, Hillary Clinton would cite Robert F. Kennedy’s assassination as justification for staying in the race.)

Exactly three days before Bill’s Charlotte remarks, Obama had given his famous “A More Perfect Union” speech in which he contrasted his ideas about race and American history with those of his former pastor, Jeremiah Wright of Trinity United Church of Christ. Wright had become a media lightening-rod after snippets of his sermons appeared on ABC’s Good Morning America.

The most controversial clip was taken from a 2003 sermon in which Wright offered this concise history of America’s treatment of “her citizens of African decent”:

She put them in chains. The government put them in slave quarters, put them on auction blocks, put them in cotton fields, put them in inferior schools, put them in substandard housing, put them in scientific experiments, put them in the lowest paying jobs, put them outside the equal protection of the law, kept them out of their racist bastions of higher education and locked them into position of hopelessness and helplessness. The government gives them the drugs, builds bigger prisons, passes a three-strike law and then wants us to sing God Bless America. No, no, no. Not “God Bless America”; God Damn America! … For killing innocent people. God Damn America for treating her citizen as less than human. God Damn America as long as she keeps trying to act like she is God and she is supreme.

You can guess which few seconds were played incessantly on every cable news network for weeks.

Wright’s pulpit politics—inspired by the Black liberation theology of James C. Cone, infused with Afrocentrism, and rooted in the lived experience of his congregation on the South Side of Chicago—were as scandalous to white audiences as they were familiar to Black ones. The idea that anti-Black racism is as much an American tradition as, say, standing and removing one’s cap for “The Star Spangled Banner”, is not a controversial opinion at many Black kitchen tables. As one Trinity Church congregant told ABC news, “I wouldn’t call it radical. I call it being black in America.”

In this and other sermons, Reverend Wright told a story of America in which violence against people of African descent was a constitutive element of American social, cultural, and economic life—where racism was not an aberration from the norm, but embedded in the norms themselves. It’s an idea with a deep lineage in the Black radical tradition, from Frederick Douglass to W.E.B. Dubois to Claudia Jones to Malcolm X to Angela Davis. Today, its best articulator (and chronicler) is Ta-Nehisi Coates.“In America, it is traditional to destroy the black body,” Coates writes,“it is heritage.” There is blood on the leaves because there is blood at the root. To change everything that needs changing, you’ve got to uproot the tree.

But that wasn’t Barack Obama’s lineage. While declining to denounce the man himself, Obama said Wright’s remarks “expressed a profoundly distorted view of the country—a view that sees white racism as endemic, and that elevates what is wrong with America above all that we know is right with America.” In its place, Obama offered a vision of an ever-perfecting union, inevitably tilting toward unity and equality. What it means to be American—to be a patriot—is to be invested in this self-improving project, to aspire to fulfill the promises of our founding documents.

“The profound mistake of Rev. Wright’s sermons is not that he spoke about racism in our society,” Obama said, “It’s that he spoke as if our society was static; as if no progress has been made; as if this country… is still irrevocably bound to a tragic past.”

As always, Obama himself—the Black man born of a white mother, married to the descendent of slaves, preaching racial unity and running for the “highest office in the land”—was the ultimate rejoinder to Wright’s pessimism. Obama’s very existence, his success, belied the idea that America was inseparable from her history of anti-Black oppression. “For as long as I live, I will never forget that in no other country on Earth is my story even possible,” the future president said.

In this manner, Obama became history’s most eloquent exponent of what Cornel Law Professor Aziz Rana calls the “creedal” story of national identity, “according to which the United States has been committed to the principle that ‘all men are created equal’ from the time of its founding, and our history can be viewed as a steady fulfillment of this idea.” Obama told a version of this same story when he was introduced to the nation at the 2004 Democratic National Convention. He has returned to it in speech after speech.

“A More Perfect Union” was a comprehensive exposition of Obama’s racial vision. Reading it now, it feels like a premonition, a place-setting, a prelude—if a misleading one—to everything that has happened in the past eight years.

But it wasn’t enough. A month later, Richard Cohen of the Washington Post wrote that in order to “put the race issue to rest” for good, Obama should give yet another speech, this one directed at white Americans and modeled on John F. Kennedy’s address about his Catholicism in 1960—in which Kennedy allayed Protestant fears that he was a Manchurian candidate for the Vatican. It’s difficult to imagine what more could be expected from Obama in this regard; Cohen doesn’t say. No matter how often he professed his love for the nation of his birth—or repeated the refrain that “there is no black America, no white America, but a United States of America”—Obama’s blackness still signified, in the white imagination, an allegiance to another country, to an alien set of values. And, in Cohen’s judgment, white people were not wrong to regard it with unease. “[Obama] did not confront white fears,” Cohen said of the Reverend Wright speech, “Instead, he implied that they were illegitimate.”

“[President Obama] has become the most successful Black politician in American history by avoiding the radioactive racial issues of yesteryear,” Coates wrote in an essay on Obama’s first term, “and yet his indelible blackness irradiates everything he touches.”

It’s remarkable, in a way, that a man who has spent his whole political career telling a story that so deeply flatters the nation’s self-conception should be the subject of such consistent suspicion—so much so that two-thirds of his successor’s supporters wrongly believe he is Muslim and 59 percent say he wasn’t born in the United States. Just as it’s remarkable that a president who has presided over 8 years of increasing luxury for the extraordinarily wealthy and a continuation of our imperial foreign policy is seen as a crypto-communist intent on sabotaging America’s global hegemony.

Probably none of this is remarkable to Jeremiah Wright.

The great irony of Obama is that the reaction to his presidency has so thoroughly contradicted the story Obama himself told us about its meaning. Some significant fraction of the white population simply never accepted the legitimacy of the first Black president. Despite his repeated public repudiations of radicalism of every kind, they insisted on seeing him as a vengeful militant, intent on subjugating whites and Christians. For eight years, the right cultivated a fantasy of white racial grievance and paranoia, fueling legislative obstruction, a resurgent white nationalist movement, and now, Donald Trump.

But another group of whites voted for Obama because they enjoyed the story he told, in which they were daring participants in a millennial project of moral renewal. Obama would inaugurate a new era of racial harmony, in which they, the good white people, would be absolved of guilt, unburdened by history. With Obama came the promise of racial redemption—preferable to the much more frightening prospect of racial reckoning.

“We were supposed to be post-racial, with the election of Obama,” said right-wing radio host Rush Limbaugh in 2015, summarizing this view, “We were supposed to have put all this behind us. His election was supposed to mean something. It was supposed to signify that we had overcome and gotten past the original sin of slavery. And instead, as I knew would be the case, it’s gotten worse.” Today, many white Obama voters are frustrated with Obama’s inability to fulfill his impossible promise. They complain that “race relations” have soured (by which they mean Black Americans have continued to protest and resist racism) and lament how little good all that talk of unity did. Some of them, we now know, helped elect Donald Trump.

Meanwhile, for non-whites, the persistence of racial inequality in wealth and income, aggressive incarceration, and racist policing have all strained the credibility of Obama’s creedal narrative. Violent white backlash—to Obama and to the Black social movements that have emerged during his second term—has belied the story of inevitable racial progress Obama told in 2008. And white America’s overwhelming support for President-elect Donald Trump has laid bare its preference to move backward, not forward—to reclaim the material and psychological privileges of white supremacy. The creedal story of national identity, says Aziz Rana, “finds itself in profound crisis.”

But as the Obama era comes to a close, a new generation of Black radicalism has emerged, one which more closely resembles the tradition the president disavowed in 2008, as a condition for winning the trust of white America. The Movement for Black Lives isn’t afraid to locate anti-Black racism at the white hot center of American culture, history, and politics. And they aren’t deluded about what would be required to abolish it.

* * *

In a way, Colin Kaepernick is poised ambiguously between these competing visions of Black politics—that of the reverend and that of his congregant.

There are two ways of viewing his protest: as an indictment of a reality that fails to live up to America’s foundational norms or as an indictment of those norms themselves. As an aspirational appeal to the American creed or a condemnation of its insufficiency, as “God bless the America that can be” or “God damn the America that is.”

Some of Kaepernick’s defenders have said that a focus on patriotism—on the flag and the anthem itself—is a distraction, mobilized by critics who don’t want to face the critique he is voicing. Certainly there’s truth to that. Kaepernick isn’t protesting the Star-Spangled Banner, after all, he’s protesting systemic racism. As Kaepernick put it, “There’s a lot of racism disguised as patriotism in this country.”

But there’s also a way in which it sanitizes Kaepernick’s protest to insist that its form is all but orthogonal to its content. Kaepernick could have called out racism and police brutality in any number of ways. A press release. A video. An op-ed in a major newspaper. Instead, he has chosen to do it in a way that directly implicates the nation and its symbols.

Kneeling during the anthem conveys something more specific than opposition to racism alone. It suggests that anti-blackness is inextricably embedded in the rituals of American nationalism, that nationalism itself is synonymous with a project of racial control. Kaepernick made this most explicit in a now-deleted social media post the night before that first pre-season game in Santa Clara. Kaepernick retweeted an image juxtaposing the Confederate and the American flags captioned “The fact that you really believe that there is difference in these flags means that you’re ignoring history.”

Ironically, racists tend to appreciate this fact. They understand, if not always consciously, that whiteness and American-ness are “fiercely paired.” It’s why they adorn their movements in the stars and stripes. Why they question the patriotism of those who criticize the racial status quo. Why they believe Obama was born in Kenya, that Colin Kaepernick is a Muslim.

If there’s something contradictory about being a white supremacist and loving America, the people who chanted U-S-A while Donald Trump insulted Muslims and Mexicans haven’t gotten that memo.

* * *

Another person who sees Kaepernick’s protest as an insult to the nation itself—its rituals, symbols, and norms—is New York Times columnist David Brooks. Brooks, despite the liberal pedigree of his employer and his fondness for the crease in Barack Obama’s pants, is an archetypal conservative: nostalgic for traditional hierarchies, instinctively threatened by dissent, and convinced that individual and collective suffering arise from moral rather than material want. Still, I often find his work instructive. The best of it offers a precise inversion of insight, a compass that points south.

In a column headlined “The Uses of Patriotism,” Brooks writes that the anthem protest reflects and perilously exacerbates a process of declining confidence in America’s “civic religion”—a “fusion of radical hope and radical self-criticism,” which over the centuries has “fired a fervent desire for change.” For Brooks, as for Obama, a shared belief in the values of the founding is what creates the conditions for change. When we sing the national anthem, Brooks writes, “we’re not commenting on the state of America. We’re fortifying our foundational creed…expressing commitment to the nation’s ideals, which we have not yet fulfilled.”

Brooks believes that by refusing to participate in these “displays of reverence” for the nation, Kaepernick and his allies make it harder to achieve the change they seek. “If these common rituals are insulted,” Brooks writes, “other people won’t be motivated to right your injustices because they’ll be less likely to feel that you are part of their story.”

A more frank and cynical formulation of Brooks’s view is this: anti-racist movements are doomed to fail unless they flatter white people’s fantasies of their own benevolence. Black people must make their democratic claims in terms of the creedal story or risk being ignored—or worse. This isn’t a exactly a novel suggestion. Movements from abolition to the Black freedom struggle have, at various times, made this strategic bargain. Martin Luther King was particularly skilled at deploying the American creed as a means of mobilizing dissent while minimizing white fear. “Martin Luther King Jr. sang the national anthem before his ‘I Have a Dream’ speech,” Brooks says, comparing King to Kaepernick, “and then quoted the Declaration of Independence within it.”

But the white response to King—like the white response to Obama—suggests the limits of an anti-racist politics rooted in the creed. White reactionaries killed King; now they use his legacy to criticize modern civil rights leaders. Obama’s time in office has inspired a resurgence of outright white supremacy, and the ascendence of a president with little apparent interest in preserving multi-racial democracy. If even the most careful, flattering critique of America’s racist reality is received by whites as an indictment of America’s most essential norms, perhaps there is something wrong with our norms.

Brooks writes, “The answer to what’s wrong in America is America,” which, unintentionally, is quite correct. America is what’s wrong with America.

Even King became disillusioned with creedal politics in the years before his assassination. In 1967, he wrote, “for the good of America, it is necessary to refute the idea that the dominant ideology in our country…is freedom and equality while racism is just an occasional departure from the norm on the part of a few bigoted extremists.” America isn’t a nation with a racism problem; it’s a racist nation. Creedal politics are a compromise with white supremacy, one that many Black social movement leaders have realized they can no longer afford.

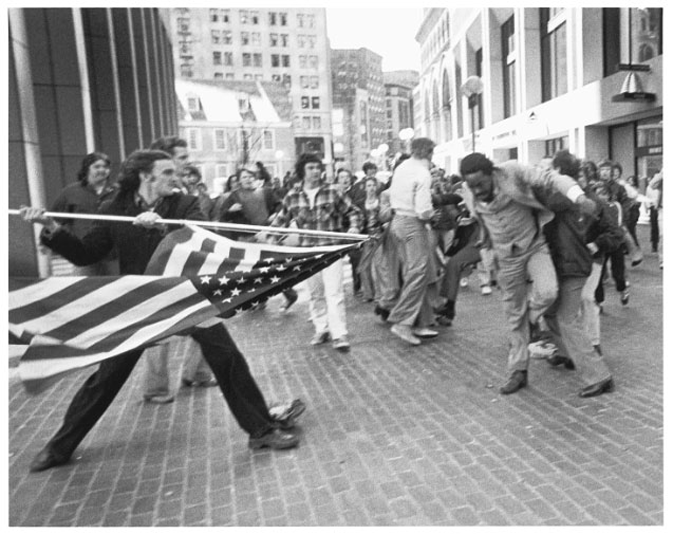

And its a myth. The creedal vision of social change is one without conflict, without winners and losers, without competing interests, in which reform movements have succeeded by the force of moral appeal alone. America has become more and more racially equitable, this story suggests, because we all agree, at least in principle, that it ought to be so. In reality, the history of Black politics is a history of the struggle to wrest unearned power and prosperity from the clutches of whites, who’ve erected a fortress of law, ideology, and violence around their privileges. Every significant siege of the fortress—from Reconstruction to Black Lives Matter—has ignited a forceful counterattack by the besieged. A white backlash.

One of the things we rarely reckon with is the fact that dismantling white supremacy is not in most white people’s immediate interest. It will require, what Martin Luther King called “a massive redistribution of economic and political power.” For whites, the attraction of the creedal narrative—in which increasing racial fairness is a natural consequence of our shared moral development—is psychological as well as material. As Reverend Wright, put it in 2015, “One of the reasons America has never confessed to its original sin is that confession means repentance, and repentance means you gotta pay.”

The difference between believers in the creedal narrative and those who see anti-Black racism as a “constitutive” element of American life is one of relative credulity in the face of American myth. The difference depends on how one reads the words, “all men are created equal” in the Declaration of Independence: as an aspiration or a lie. David Brooks believes it’s an aspiration, the moral principle that has guided and motivated what Obama called in 2008, “the long march… for a more just, more equal, more free, more caring and more prosperous America.” Reverend Wright says it’s a lie. “The truth was they believe all White men were created equal. The truth is they did not believe that even White women were created equal.”

In Where Do We Go From Here?, published just before his death, King wrote, “In the days ahead we must not consider it unpatriotic to raise certain basic questions about our national character.”

We must begin to ask, “Why are there forty million poor people in a nation overflowing with such unbelievable affluence?” Why has our nation placed itself in the position of being God’s military agent on earth…? Why have we substituted the arrogant undertaking of policing the whole world for the high task of putting our own house in order? All these questions remind us that there is a need for a radical restructuring of the architecture of American society… For the evils of racism, poverty and militarism to die, a new set of values must be born.”

A variety of patriotism that rejects militarism, racism, and capitalist orthodoxy, would indeed be, as King says, “a new set of values”—unrecognizable as the patriotism that today is used to silence and stigmatize dissent, to paper over America’s racist reality. Instead of sanitizing the past, it would reckon with it. Instead of washing the blood off the leaves, it would address the blood at the root. It would entail, as King says, “a radical restructuring of the architecture of American society.”

* * *

The final, redemptive verses of Hughes’ “Let America Be America Again” are instructive:

O, yes, I say it plain,

America never was America to me,

And yet I swear this oath—

America will be!Out of the rack and ruin of our gangster death,

The rape and rot of graft, and stealth, and lies,

We, the people, must redeem

The land, the mines, the plants, the rivers.

The mountains and the endless plain—

All, all the stretch of these great green states—

And make America again!

The task for today’s anti-racist movements is to remake America on new ground. Not by recovering the values of America’s past. But by radically imagining America as it never was. The preamble to the comprehensive Movement for Black Lives platform captures this spirit: “We have come together now because we believe it is time to forge a new covenant.” (Not to fulfill the promises of the old one.)

America never was, but it could be. As Colin Kaepernick recently said, “Let’s make America great for the first time.”